The Three North Program, or “Sanbei”, is one of the biggest ecological conservation efforts in restoring plant coverage. Since its launch in 1978, Sanbei has aimed to restore plant coverage in almost all parts of northern China, particularly the arid areas in the northwest, to improve adverse environmental conditions in northern China, such as severe soil erosion and frequent episodes of sand and dust blowouts that had long disrupted local agricultural activities. As of 2020, Sanbei had completed the first two phases of its 1978-2050 plan. Now in its third phase (until 2050), the program has evolved from the massive planting of single tree types in the early stage to more science-based, comprehensive approaches that involve restoring various plant species tailored to local environments.

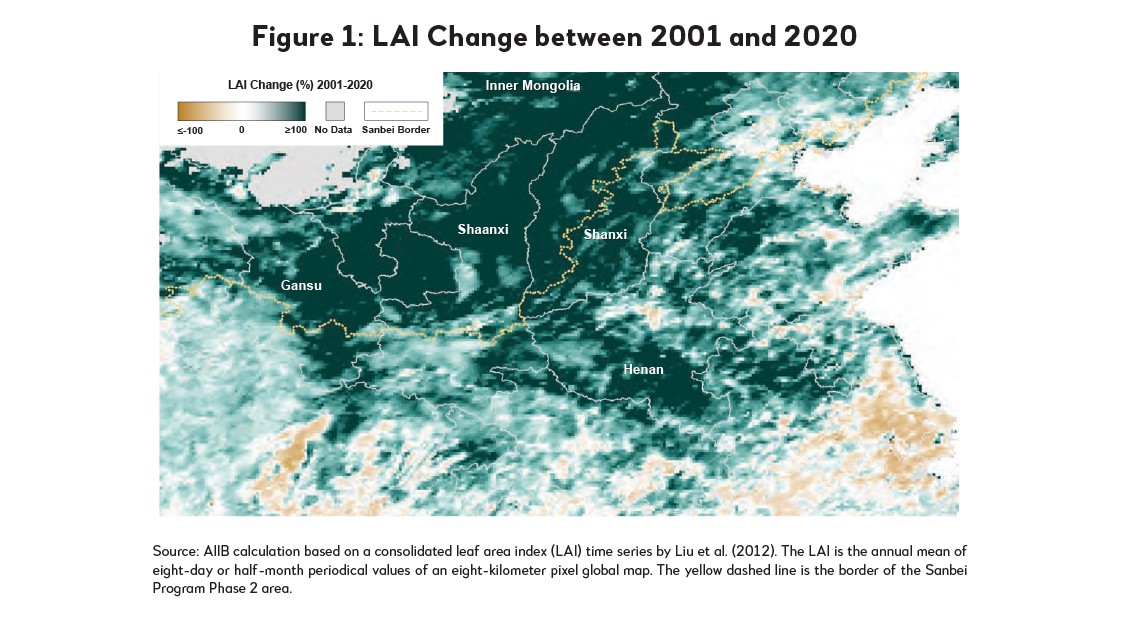

Both official and international geospatial data show that Sanbei has contributed to the greening of northern China in the past four decades. Between 1978 and 2017, the forest coverage rate in the Sanbei area increased from 5.1% to 13.6%. Grass and forest coverage rate increased from 31.7% to 42.4%. Leaf Area Index (LAI), a measure of thickness of leaves per unit area, also increased in much of the area covered by Sanbei Program, particularly in the Shaanxi, Shanxi and Heilongjiang provinces. The area plagued by soil erosion declined by two-thirds or by 44.7 million hectares. Furthermore, deserts in northern China seem to have stopped further expansion since 2000. Some areas have also seen a reversal of desert conditions.

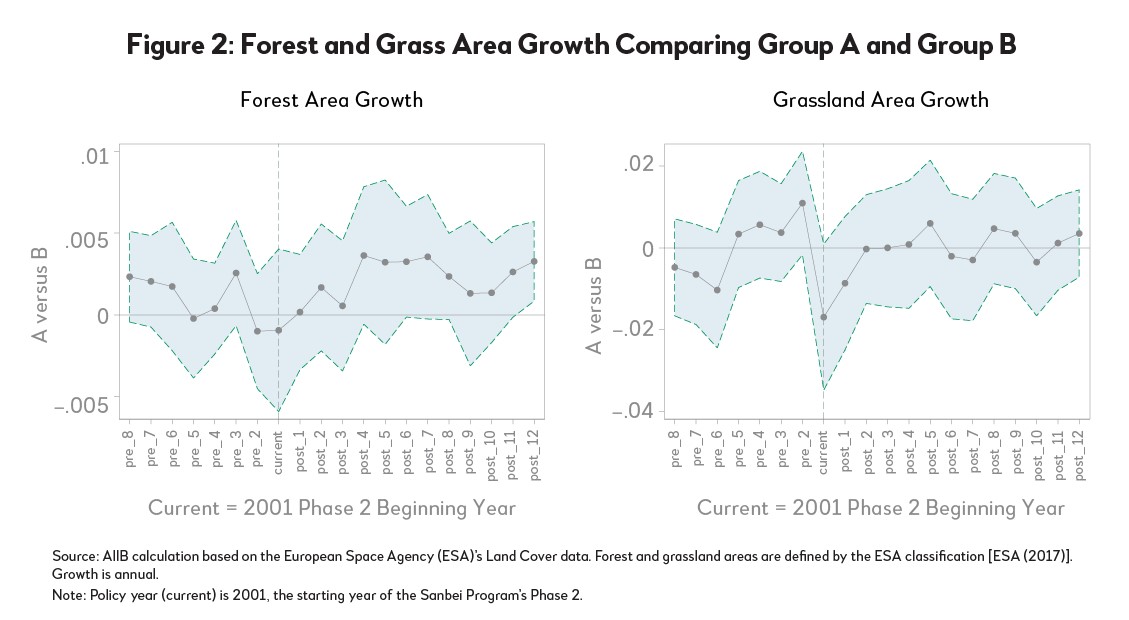

Restoring the Green Great Wall requires strategic patience, as it takes many years before the positive impacts are felt (especially in areas where local ecological conditions were vulnerable to begin with). By selecting two comparable groups of locations alongside Sanbei border, we compared LAI as well as total forest/grassland area growth[1] using the event study method. Results are mixed, with total forest area growth slightly faster in Sanbei counties than the control group south of Sanbei region. Growth of grassland also appears to be similar between the two groups before and after 2001 when Phase 2 of Sanbei started. LAI also only saw higher levels in the early 2000s in Sanbei. Quite simply, forest and grassland growth took time, particularly in northern China where the ecological systems in arid areas are highly vulnerable.

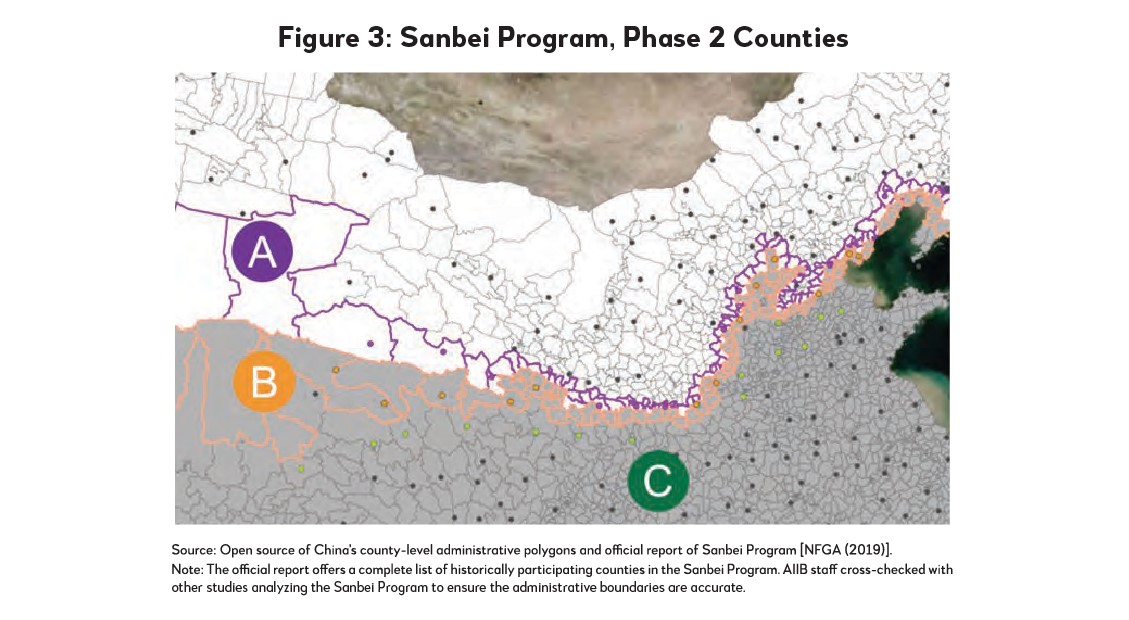

Due to data availability, the analysis focuses on Phase 2 of Sanbei (2001–2020). During these two decades, 725 county-level administrative areas were assigned to be part of the program, including all the 551 counties that already participated in Phase 1 during 1978-2000. The key research design is one of border discontinuity, exploiting the differences between the program countries (A) bordering non-program countries (B), (see Figure 1). As explained later, there is also a need to check against data in counties further south (C).

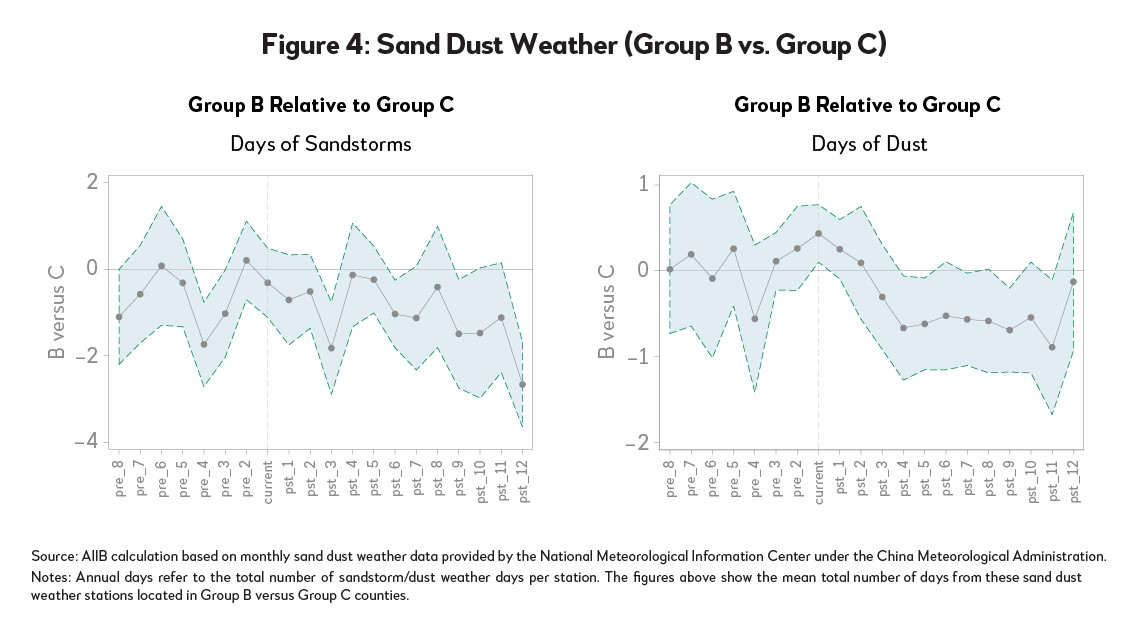

The program reduced dust conditions in counties south of the planted trees, outside of the Sanbei area. From the beginning, restored forests and grasslands were expected to control desertification and sand dust weather in northern China. Meteorological data suggests that dust conditions have become weaker in areas south of the Sanbei area–highlighting how its policy impact can spill over beyond the participating counties. The analysis also underscores the challenges of measuring and evaluating the impact of ecological conservation projects. The outcomes, such as sand dust, are often deeply affected by broader climatic factors (e.g., changing atmospheric pressure, precipitation) where human greening efforts have little control.

Restoration of forests and grasslands on such a massive scale, particularly in those ecologically vulnerable areas, has been physically and financially daunting over the past four decades. There are key lessons to be learned.

- Engaging local communities in nature infrastructure, especially project maintenance, is key to project sustainability in the long run. Unlike other infrastructure, nature infrastructure such as Sanbei is built and maintained by local residents (e.g. through planting, irrigation). This will require a combination of policy incentives, including fiscal support in the short term and commercialization of the agricultural values (e.g., of Sanbei forestry assets) that can provide sustainable income to local communities.

- Deepening scientific knowledge and applying it to local conditions is essential. Science is essential to project success. The right plant species must be deployed in the right conditions. Scientific studies can help us understand where, and how much human intervention is needed to successfully restore the local ecological system. Climate change impact also means that this knowledge has to be constantly updated.

- Complementary conventional infrastructure is needed. The sustainability of the green belts requires irrigation, water management, and roads to transport necessary resources. These too require sufficient funding support.

- The financial sustainability of ecological conservation projects rely on their integration into economic sectors. The agriculture sector (e.g. forestry, fruits) remains the main starting point, but people are also seeking other innovative solutions such as solar farms in planted grassland.

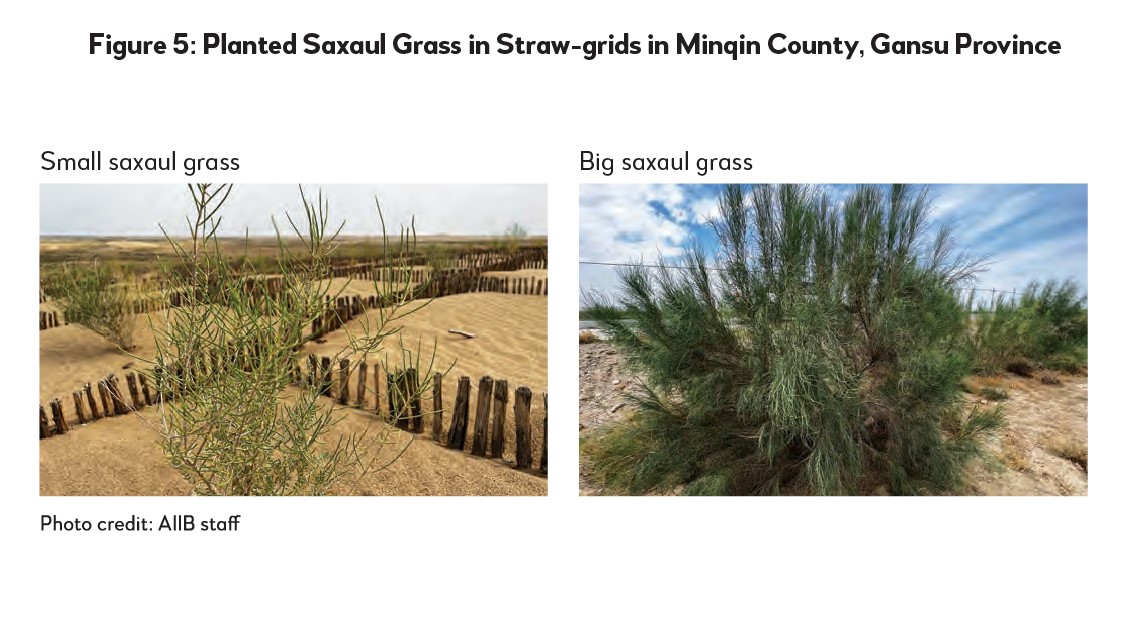

Source: AIIB staff. Saxaul grass is replanted in straw-grids called caofangge, which is widely used in Minqin County in Gansu Province to affix sand. This technique is one way to stop sand from being blown away by wind to form sand dust.

Note: This blog is adapted from Chapter 4 of the Asian Infrastructure Finance 2023: Nature as Infrastructure, one of AIIB’s flagship publications. The full report can be downloaded here.

[1] European Space Agency Landcover data series.