Firms are often hit by environment, social or governance (ESG)-related controversies or damaging disclosures. The reaction of markets to negative disclosures can be a powerful tool to nudge firms toward responsible behavior. Controversies can be broadly categorized into environmental, social and governance issues. However, the magnitude of the reaction depends on how well the market can price in the risk from a controversy. Past studies have documented the effect of climate-related disclosures and natural disasters on specific markets and financial instruments (e.g., corporate bond spreads). In this analysis, we take a cursory look at the impact of ESG-related controversies on company stock prices using globally representative data. Given the increased call for better disclosure requirements related to nature-related risks, we shed some light on whether and how markets react to nature-related controversies.

This analysis uses Moody’s Controversial Activities Screening database, which documents ESG-related controversies covering 4,000 firms. Controversies are categorized into “minor (12%)” “significant (52%)” “high (34%)” and “critical (1.4%)”, in the order of increasing severity. By searching keywords, it allows us to categorize controversies into themes, e.g., nature-related controversies8.

We compare the stock prices of firms hit by a ‘critical’ controversy vis-à-vis firms that are not hit by a critical controversy—the differences in stock prices could be interpreted as the “controversy effect”—how much stock prices suffered due to the critical event.[1] We limit our analysis to the controversies that occurred post-2015. Further, we limit our sample to the initial controversies which allows us to separate the effects arising from the subsequent events.[2]

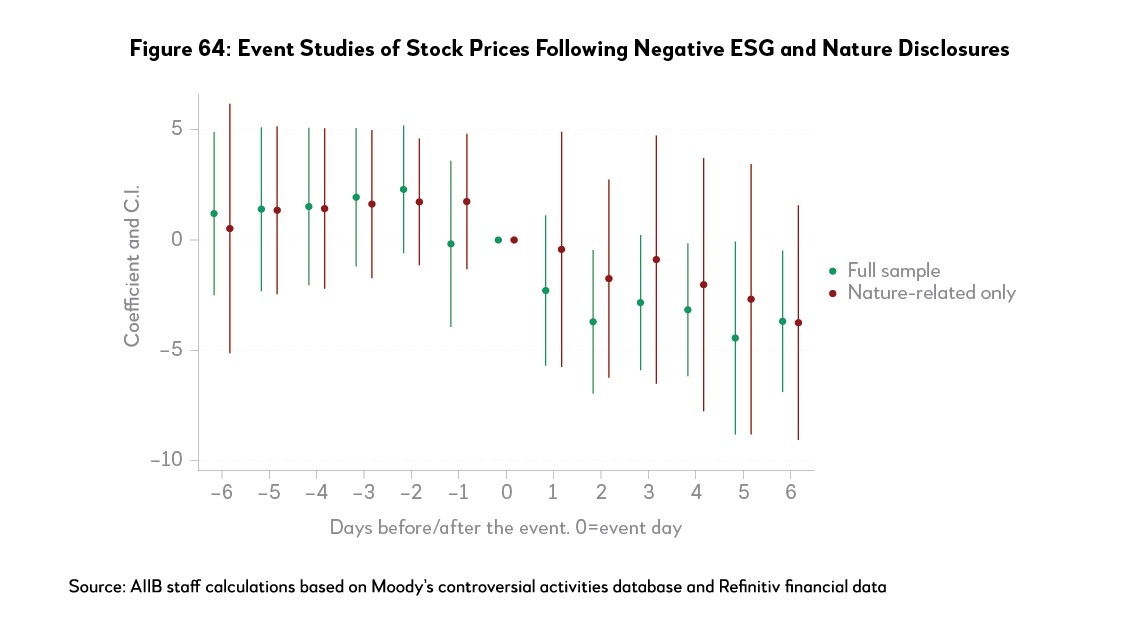

The chart below reports the magnitude of the impact of the controversy during a 13-day window around the controversies (six days before and six days after) for affected firms relative to other firms after controlling for company-specific factors and macroeconomic factors that may affect the stock prices. Firms with ESG-related controversies, on average, suffer a four-percentage point hit to their stock returns (yearly return) during the six days after the event. Figure 1 shows the time evolution of this effect. The hit on stock price persists until six days post-controversy (the end of the “event window” in this study).

CI = Confidence interval

Source: Moody’s controversial activities dataset and Refinitiv financial data with calculations by AIIB staff.

Amongst the ESG-related controversies, environment-related controversies have the largest “controversy effect,” followed by governance-related and social-related controversies. Within environment-related controversies, however, nature-related controversies do not seem to have a significant negative impact on stock prices. Many factors could drive such a result. For example, the average intensity of nature-related controversies may be lower than other environmental controversies. Second, there could be information asymmetry in the financial market for nature-related risks. Lastly, the market cannot price nature-related risks due to the lack of frameworks, disclosure requirements and financial instruments.

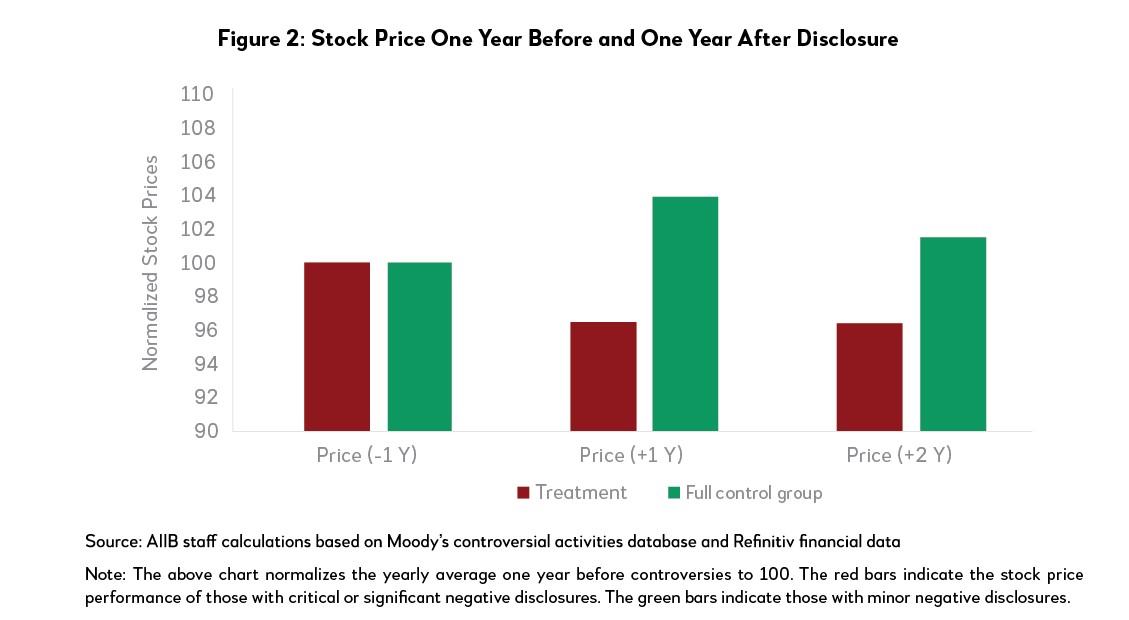

Given that we find some effect of the controversy on stock prices during the 13-day window, we next ask: how long does the effect last? More generally, do firms with higher ESG risk perform worse in the medium to long term? To assess the long-term impact of stock prices, we compare the yearly average stock price one year after the controversies happened versus one year before the controversy. For the firms hit by critical controversies, the average stock price was four percentage points lower in the year following the controversy (Figure 2).

Since stock prices are affected by many factors during a longer period, this result is not meant to be interpreted as causal. Nevertheless, it provides preliminary evidence that corroborates with studies that have found that nature-related risks can lead to financial risks through the feedback loop—a reduction in ecosystem services leads to production reduction, translating into a deterioration of financial position.

Overall, we find that ESG-related negative disclosures affect the stock prices, suggesting market’s role as a “deterrent”. However, the role of the market itself is not sufficient to mitigate nature-related risks. Assessing the value of nature and biodiversity is a daunting task, as “the assessment must take into account the perspectives of the humanities, of developing countries and of members of indigenous communities”.[3] Different instruments, such as taxes and subsidies, offsets, and tradable permits have been developed. There needs to be effective local regulations and enforcement. Unlike greenhouse gas emissions with the same global externality regardless of the source of emission, nature and biodiversity are “hyper–local.” Nature and biodiversity are differentiated everywhere, with complex linkages. Setting a single price (unlike a single carbon price) will be more difficult. This also implies that regulations need to account for local factors and will have to be differentiated, which would only be possible with proper data and research. Enforcements could also take the form of standards and labeling specific to nature outcomes. Such non-price policy levers can help producers and consumers make informed choices.

Note: This blog is adapted from Chapter 8 of the Asian Infrastructure Finance 2023: Nature as Infrastructure, one of AIIB’s flagship publications. The full report can be downloaded here.

[1] In this study, we are comparing firms that are hit by critical controversies and firms that are not. Ideally, the comparison should be done between firms that are hit by controversies and those that are never hit, essentially all listed firms. However, our data set contains firms hit by some controversy during the period. But controversies do not hit the firms at the same time. If a critical controversy hits a firm, it is unlikely in the data that another firm gets hit by controversy on the same day. We are also restricting the sample to a 14 day-window and ensure that no other controversy hits another firm within that window. Essentially, when a controversy hits a firm, all other firms (regardless of whether they get hit or get hit by a controversy later or earlier than the 14-day window) can serve as the control group.

[2] In Moody’s data, it records the initial event (the outbreak of a controversy), as well as the updates (for example, the company’s reaction, settlement after a lawsuit, etc.). In this study, we remove all the updates of the controversies from the analysis, limiting the “event” to only the outbreak of the controversy.

[3] See https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02882-0