Coastal populations worldwide, especially in Indonesia, the largest archipelago in the world, face significant risks of tidal floods due to rising sea levels. As of 2022, Indonesia’s sea level has surged by a staggering 200 millimeter (mm) above 1992 levels, while the coastal population has increased from 35 to 55 million in the last three decades. Scientific evidence suggests that mangroves are essential for mitigating the risks posed by tidal floods.[1] As per the World Bank’s mangrove valuation framework, Indonesia has emerged as one of the countries experiencing the highest surge in the value of mangroves between 1995 and 2018, primarily attributed to the country's elevated flood risk.

According to the Global Mangrove Watch, Indonesia has about 23% of the world’s total mangrove area, equivalent to about 3.5 million hectares in 2008. Mangroves are distributed along the coastlines of 265 out of 301 coastal regencies in Indonesia.[2] Yet compared to other areas, areas without mangrove cover, predominantly located on the southern side of Java Island and the northwest region of Sumatra Island, remain vulnerable due to their lack of natural coastal defense near heightened tidal flood risks.

Mangroves do not reduce the occurrence of tidal floods, but reduce the damage caused by the floods. On average, approximately 25% of the regencies lacking mangrove coverage encounter tidal flood disasters at least once every five years, while only 16.5% of the regencies protected by mangroves have the same frequency of flood occurrence. Although, we do not find a statistically significant impact of mangroves on tidal floods, we find a statistically significant and positive association between higher mangrove coverage (within a five-kilometer (km) buffer area from the coastline) and lower damages caused by floods.[3] On average, a regency with higher mangrove cover by 5.6 percentage points saves one amenity from being damaged during tidal floods.

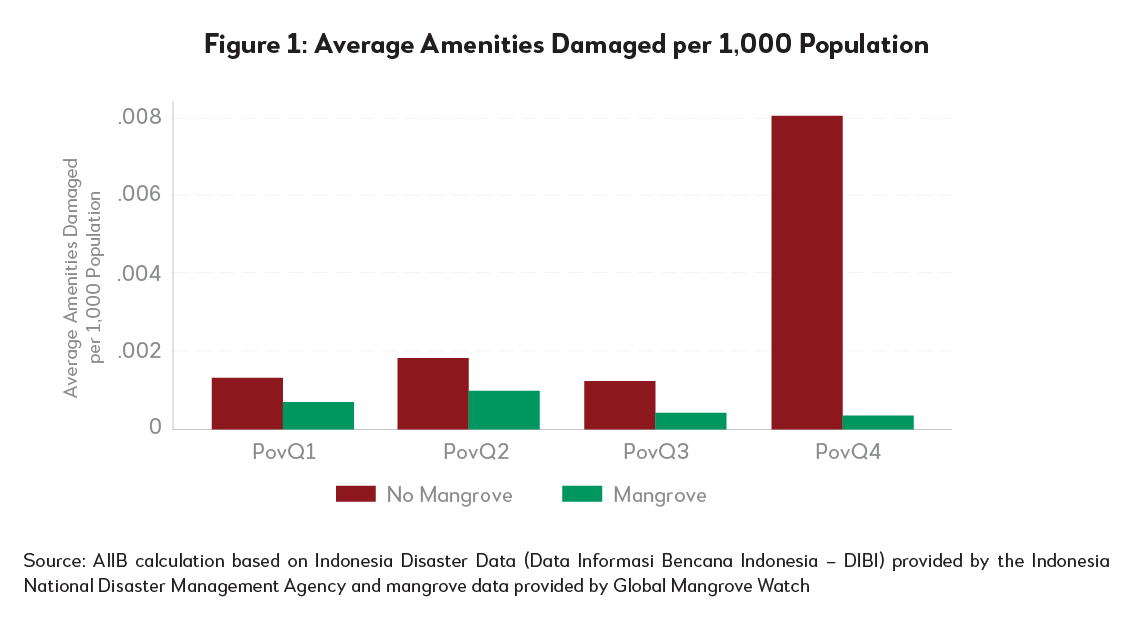

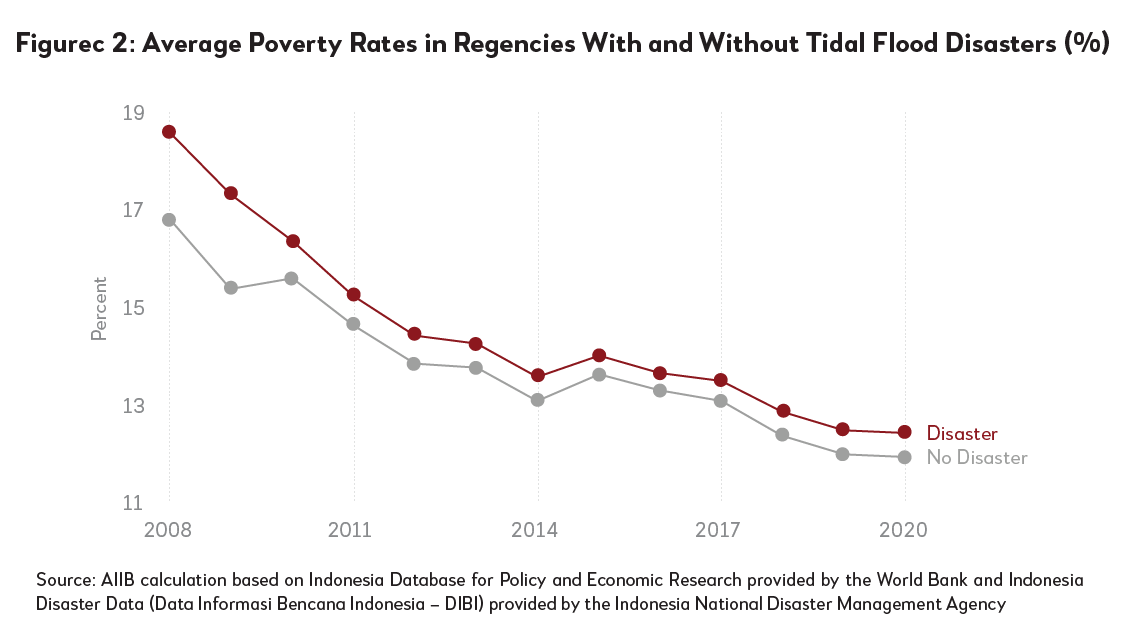

Poorer regions with no protection from mangroves experience higher damages (Figure 1). On average, approximately 8 units of amenities are damaged per 1 million inhabitants in these impoverished regions. By contrast, regencies endowed with mangroves experience only 0.3 units of amenities damaged per 1 million population. Additionally, tidal floods occur more in regions with higher poverty rates. (Figure 2). These findings underscore the need for effective mitigation measures to prevent vulnerable populations from plunging further into poverty due to tidal flood occurrences.

|

|

|

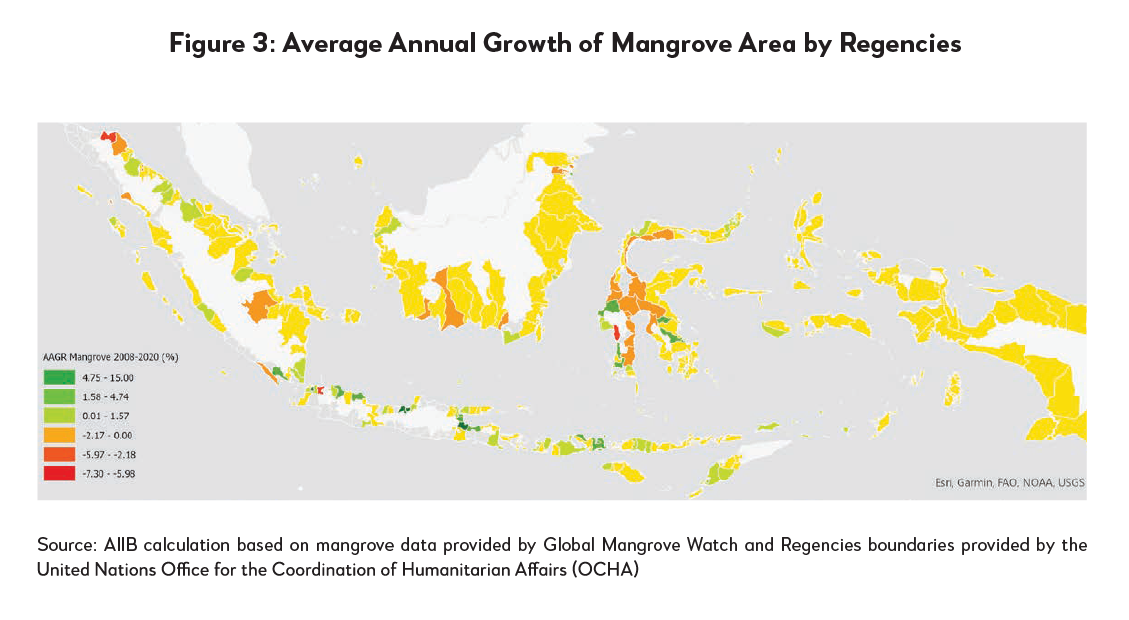

Despite having the world's largest mangrove cover, Indonesia lost over 60,000 hectares of mangroves between 2008 and 2020. This depletion is most severe in regions undergoing rapid industrialization and mining, predominantly on the islands of Sulawesi and Borneo (Figure 3).

Regencies with depleting mangroves experience more amenities damaged compared to those with expanding mangroves. Our analysis finds that the correlation between damaged amenities and mangrove cover is stronger in regencies with growing mangroves (the first subset) compared to those with depleting mangroves (the second subset), both relative to regencies with no mangroves. For each one percentage point increase in mangrove coverage within a five-kilometer buffer area from coastlines, there is a reduction of 0.4 units of damaged amenities in regencies with growing mangroves. In contrast, in regencies experiencing mangrove depletion, there is a reduction of 0.2 units of damaged amenities for each percentage point increase in mangrove cover. This difference between regencies with expanding and shrinking mangroves may be attributed to the spatial distribution of built-up development and mangrove conservations. Regencies lacking effective conservation measures might experience population growth within high-risk tidal flood areas, encroaching upon mangrove habitats.

Given the transboundary nature of mangroves, cross-sectoral and multistakeholder collaboration is essential for successful preservation, including local and central government bodies, planning agencies, environmental organizations, and disaster management authorities. This collaboration is enabled by establishing clear mandates and responsibilities among these entities, which to some extent, depend on the capacity of the local governments. Among regencies classified as lowest government capacity, roughly 62% experience mangrove depletion. On the other hand, only 33% of regencies with the highest government capacity experience mangrove depletion. Effective mangrove conservation requires collaborative efforts spanning governmental bodies, institutions, and local communities. To this end, financial and technical capacity building at different administrative levels become important.

Note: This blog is adapted from Chapter 4 of the Asian Infrastructure Finance 2023: Nature as Infrastructure, one of AIIB’s flagship publications. The full report can be downloaded here.

References

Krauss, K. D. (2009). Water level observations in mangrove swamps during two hurricanes in Florida. Wetlands, 29(1), 142-149.

Resio, D. A. (2008). Modelling of the physics of storm surges. Physics Today, 33-38.

Westerink, J. L. (2008). A basin- to channel-scale unstructured grid hurricane storm surge model applied to southern Louisiana. Monthly Weather Review, 136(3), 833-864.

[1] Mangroves increase the frictional resistance of the land surface, slowing the rate at which water flows inland and steepening the surge front [Resio (2008)]. Site–specific studies show that mangroves reduce the water level in wetland areas during hurricanes in Florida [Krauss (2009)]. Additionally, mangroves also buffer the water surface from the effects of wind, thus reducing the generation of wind waves, wave set–ups and wind run–ups [Westerlink (2008)].

[2] Coastal regencies are defined as regencies where parts of its borders are coastlines.

[3] Ibid.