Climate change intensifies the spread and impact of water- and vector-borne diseases (WVBDs) like dengue, malaria, diarrhea, leptospirosis and Zika virus by increasing the survival and dispersion of pathogens and vectors, and by disrupting health infrastructure. All humans face some level of exposure. However, not everybody is equally affected. Recent research shows that women are disproportionately exposed to WVBDs mainly due to occupational roles and rigid gender norms. As a result, health outcomes between men and women differ substantially, with severe implications not only for women’s well-being but also for public health in general.

In India, health data indicates that women endure a larger prevalence of WVBDs than men. Indian women account for 18.8% of global Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALY)—a measure of years of life lost due to premature death or diseases due to WVBD—compared to a standardized life expectancy. In comparison, Indian men account for only 16.5% of WVBD-related global DALY. The difference is even more pronounced among the working-age group (15-69 years).

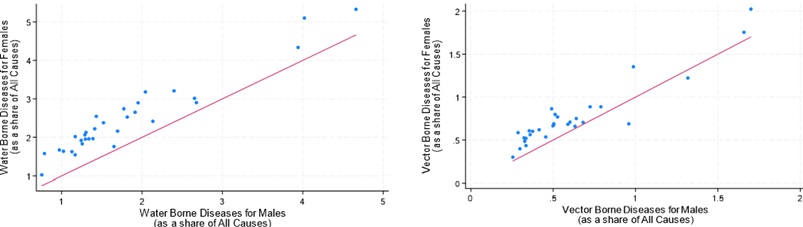

A breakdown of the aggregate numbers indicates that the divergence is pervasive. Across all the major Indian states, the prevalence of water-borne diseases is higher for women than men, as evidenced by the blue dots (each representing a state) lying above the 45-degree line (Figure 1a). The scenario is marginally better for vector-borne diseases, where aside from Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh, women consistently face higher disease burdens from WVBDs than men (Figure 1b).

Figure 1: Gender Differences in Water and Vector-borne Diseases in India

Source: AIIB staff estimates and Global Burden of Disease Data.

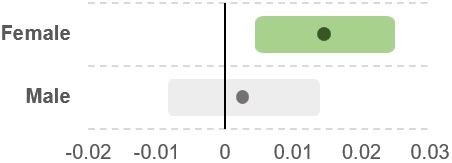

In Indonesia, comparing regencies experiencing annual flooding with those that do not also reveals that women are more vulnerable. Figure 2 shows that in a city with a one-million-person population, 150 additional cases of waterborne diseases among women would occur following a flood. At the same time, there would be no discernible effect on men.

Figure 2: Probability of Contracting Waterborne Diseases Post-Flood by Gender in Indonesia

Source: AIIB Staff estimates.

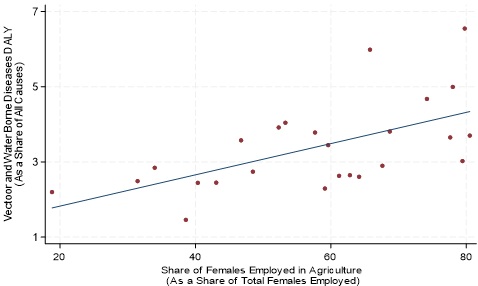

What are the factors behind this outsized impact on women? The first relates to the distinct differences in the environments where men and women work. Women workers tend to be overrepresented in natural resource-based and climate-vulnerable sectors. For example, 63% of female workers in India are employed in agriculture, compared to only 46% of men. Women in agriculture work long hours near stagnant water, making them susceptible to diseases like malaria and dengue, which spread in and around water bodies. Similarly, proximity to livestock increases susceptibility to zoonotic diseases like avian influenza. Thus, it is unsurprising that states with high female agricultural participation tend to report a correspondingly higher prevalence of WVBD DALYs among women (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Female WVBDs DALY and Female Participation in Agriculture in India

Source: AIIB staff estimates.

A second factor driving the divergence is related to women bearing the primary responsibility of fetching water for household activities. Flooding and drought conditions often lead communities to rely on contaminated water sources, with women at a greater risk of exposure to these hazards. In less developed parts of Indonesia, such as Nusa Tenggara and Papua, as well as rural areas, the task of fetching water falls primarily on women and children. This sustained contact with potentially contaminated water sources increases their vulnerability to diseases, particularly in poorer regions with limited clean water access and inadequate infrastructure.

Moreover, pregnant women face additional health challenges from WVBDs that go beyond those experienced by others. Diseases like dengue and Zika virus carry the risk of severe complications for pregnant women, potentially leading to preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction and fetal health issues such as microcephaly and impaired cognitive development. These risks compound the general health impacts of WVBDs, adding another dimension to the vulnerabilities faced by women.

Third, inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure amplifies these risks. In developing countries, limited access to clean water and proper sanitation disproportionately affects women, especially during menstruation and pregnancy, when hygiene needs are heightened. Poor access to clean facilities increases the likelihood of infection, both from WVBDs and other diseases, adding further strain to women's health and the healthcare system.

Finally, women face significant barriers to healthcare access beyond these environmental and infrastructural factors. In many regions, healthcare facilities are scarce, particularly in rural areas. Even where facilities are available, access to them is often limited for women due to various social and economic barriers. For example, transportation challenges can prevent women from reaching medical centers for timely care, leading to delays in treatment and a worsening of symptoms. These barriers perpetuate a cycle of inequality in which women’s health needs are consistently under-served, exacerbating the already high health disparities between men and women.

The links between WVBDs, climate change and gender underscore the need for gender-sensitive policy interventions in climate adaptation and disaster preparedness. Policymakers must explicitly address the disproportionate risks that women face from WVBDs in their adaptation and mitigation strategies. Failing to do so risks worsening gender inequalities and undercutting efforts to build resilience in communities affected by WVBDs.

In addressing these challenges, there are several key areas where gender-responsive policy planning could make a significant impact. First, implementing gender-sensitive disaster preparedness plans can better protect women during extreme weather events, helping them access clean water sources and safe shelter in times of crisis. Occupational health should also be enhanced to include protections for women working in high-risk sectors like agriculture, with specific measures to reduce exposure to disease vectors. Promoting nutrition security for women, especially in rural communities, is also essential to support their immune health, particularly as they bear the brunt of WVBD exposure. Finally, expanding access to healthcare services in underserved areas would help bridge the healthcare gap that leaves many women vulnerable to preventable diseases.

Empowering women and prioritizing their health needs in WVBD and climate resilience strategies will benefit women and the communities that depend on their well-being. When women are supported in maintaining good health, the positive impacts extend across families, workforces and entire communities. As efforts progress toward a future resilient to climate change and public health threats, it is crucial to ensure that gender-sensitive approaches are integral to policies, strategies and interventions.

This article is adapted from Chapter 3: In Deep Water—Climate Change Impacts on Water Systems and Human Health of the report Asian Infrastructure Finance 2025: Infrastructure for Planetary Health.